Why China’s “super-apps “ will never succeed in the US

“There’s no Skype, no Facebook, no Twitter, no Instagram, we use WeChat. OK Tell me your WeChat number!” — Higher Brothers, WeChat

The copycat of technology from the West that was China’s tech industry in the past, is dead. And it wasn’t curiosity that killed it. In fact, as China’s tech has evolved from these carbon-copy replicas restamped and rebranded with cheesy graphics and Chinese characters, much of China’s tech has become the central attraction for tech hubs around the world. The emergence of amazing all encompassing capabilities and incredible pervasiveness of apps like WeChat and TaoBao are shifting eyes towards China as the central attraction.

The question that everyone is asking is : Can something like WeChat dominate here in the US?

My answer is no.

I’ll take a dive into 3 cultural and historical aspects that highlight the key differences between the emergence of WeChat as China’s super-app and the individual app heavy tendency in the US.

For a great introduction to this shift in Chinese tech and a video introduction to WeChat, check out the NYT video above.

Why care about WeChat?

Tencent’s super-app WeChat, the messaging app of China (if we can even call it a messaging app) has tech companies, analysts, and media outlets up in arms trying to understand its incredible success and dominance in the Chinese tech landscape. Since it’s release in 2011, it has since become one of the world’s largest standalone apps, with over 1 billion monthly active users. In May 2017, CNBC reported WeChat received on average 29% of all time spent on mobile devices. In comparison, the most used app in the US, Facebook, that same year reached 19% of time spent on mobile phones.

Even more astounding is the complete market dominance WeChat has achieved domestically. WeChat accounts for around 90% of all messaging app users in China, while Facebook’s messenger doesn’t even touch upon 30% in the US.

So why has WeChat become so unbelievably dominant in the Chinese tech space? Much of this can be attributed to its establishment as a super-app. In today’s China, WeChat isn’t just another messaging app. It’s necessary to survive.

Understanding what really is WeChat: The anatomy of a super-app

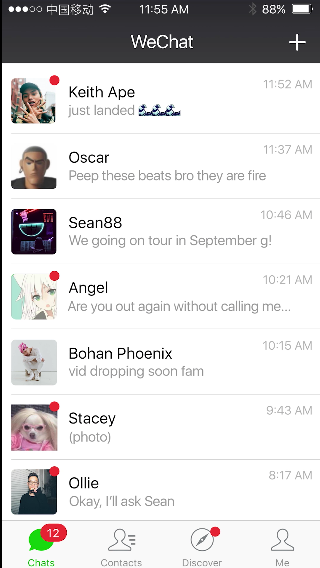

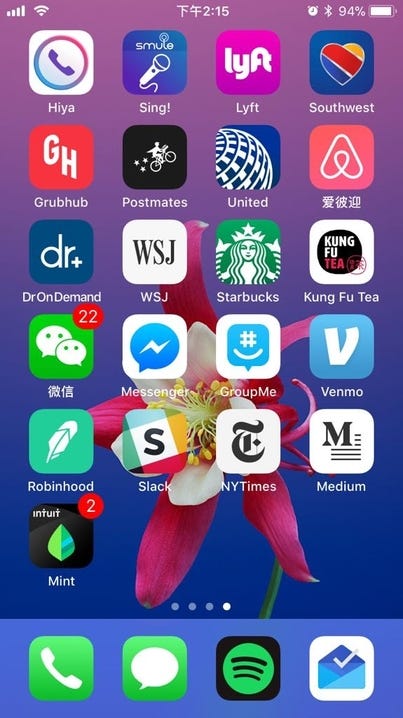

Here’s one of my many phone screens:

I think this a typical look into mobile phone users in the United States.

I have an app or two for reading the news, an app for each of my most used airlines, a few options for ordering food on the go (gotta grab those discounts), some company specific customer loyalty and order ahead of time apps, an app to call a ride share, and some personal messaging and recreational apps.

When I’m looking to do something that one of my current apps can’t, I’ll just find something new on the App Store to take care of that.

On the other hand, here’s a preview of a typical Chinese phone user’s phone screen.

WeChat or WeiXin.

Obviously I just moved all my other apps to a different screen on page, but WeChat really does provide for an all encompassing mobile experience. Through in TaoBao, Mobile Baidu, UCBrowser, YouKu, and some popular livestreaming app, and that might capture the most popular apps for an average Chinese consumer.

But let’s take a quick look at the anatomy of WeChat itself, and how it serves such a diverse set of needs.

What characterizes a super app is its seamless, integrated experience to major online hubs, bypassing individual company websites and disparate interfaces.

Here are 5 key screens that capture the expansive and diverse set of WeChat’s functionality.

WeChat Wallet

Once you have registered with a credit card or bank account, you can use all of WeChat’s available financial services. From here you can:

- Buy train tickets

- Purchase and manage city services: pay for utilities, book a doctor’s appointment, and even pay for traffic fines (what!?)

- Hail a ride share

- Order takeout

- Get a bike share

- Book a stay at a hotel

And a whole lot more.

WeChat “Take a look”

An algorithmically curated news feed for important news, interesting posts, and content that you might want to read.

WeChat/JD Shopping

An in app shopping marketplace provided by JD, one of the largest ecommerce platforms in China.

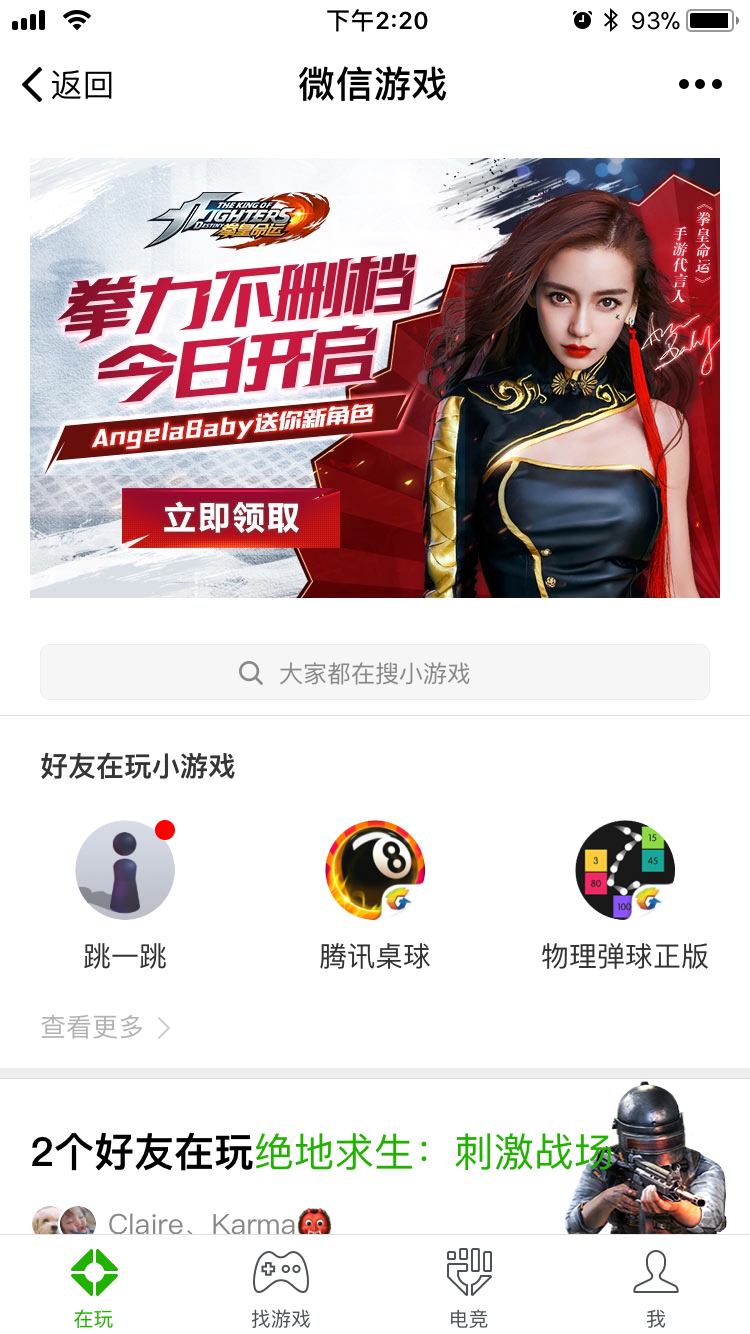

WeChat Games

As WeChat is developed by Tencent (as in Tencent Games, the world’s largest and most valuable gaming company, Arena of Valor, Riot Games), WeChat naturally has a huge suite of games and gaming ecosystem right within the app.

WeChat Mini Apps

In 2017, WeChat launched the Mini Program or Mini App feature which allows developers to develop apps within the WeChat ecosystem. They are typically reduced functionality, disposable apps that can take advantage of info already within the WeChat ecosystem, like payments, and maintain a consistent user interface. Rather than having to download an app and worry about storage limitations, Mini Apps are more like Google’s Accelerated Mobile Pages within WeChat, so they are transient.

For example, Tesla has a mini app to help users locate Tesla charging stations and find other Tesla services.

WeChat Mini Apps might be the biggest proof of WeChat’s success in penetrating and dominating all aspects of Chinese life. Instead of just developing for the traditional device specific app store, with WeChat, companies are putting their apps within an app.

Not pictured above

WeChat still primarily serves as a messaging app. The screenshot at the very top of this post shows a picture into the messaging interface, where you can be a part of groups, message individual people, and follow Official Accounts. WeChat also has Moments where you can share statuses and multimedia with your contacts.

The design of the social pieces of WeChat are interesting in their own right, but that’s for another post!

Without skipping a beat, pressing home, or visiting some other external landing page, and without being redirected into another app altogether, WeChat has curated a way for a user to message friends, shop together, eat lunch together, and get together all in one.

With this brief overview of WeChat, we have enough information to talk about the important story at hand: why China’s super-apps, like WeChat, will never succeed in the US.

The first stop: how the app ecosystem developed in China as compared to that in the United States.

Developing the app: Two different ships across the sea

Why is the US app market so fragmented, with new services and companies vying for the mobile phone customer’s attention seemingly every few months? Why have Tencent along with a few other internet companies been able to seemingly completely suffocate all other attempts to compete in the mobile phone space in China?

We have to take a look at their histories.

The US: An established, diversified internet ecosystem

The iPhone. I don’t even need to find a good free to use iPhone 1 picture for you to recognize this phone.

The iPhone changed the mobile phone landscape forever. With the 2008 launch of the App Store featuring 552 applications from both Apple and other 3rd party developers, we had the first device that turned the phone from a texting and talking device with a few “smart” capabilities, into a platform.

The App Store was the first smart phone. But what exactly constituted this new platform?

A few months after the release of the App Store, TechCrunch released a list of top early downloads.

The top downloaded apps, in order, were:

- Remote

- AIM

- Google Mobile

- eBay Mobile

- Twitterific

- NYT

- Myspace mobile

- AOL Mobile

- Pandora

The app environment was defined exactly by the preexisting internet environment and how these customers were already accustomed to the internet.

As people moved from the browser to phones, these primarily desktop browser users expected phones to be a continuation of that experience. Where in the US, the internet world had already led rise to heavy competition between Facebook, Myspace, and a newly rising Twitter. Google had already taken up the search space and online news sites for each media outlet were gaining traction.

Separate internet bubbles had already formed in the eyes of the US internet consumer. Competition just to dominate in one space was incredibly tight, and companies focused their best efforts to succeed where they had captured one area of customers’ attention. By the time companies like Google, Facebook, Apple had accumulated enough cash and runway to be secure in search and ads, social media, and consumer electronics respectively, there were already other companies blazing the way for the share economy, music, bike sharing, health, finances, and all else. For these tech giants to then try to create a viable competitor, we either had attempts for acquisition (Instagram, Oculus, Youtube, Waze, etc.), or Google+.

So individual apps were the byproduct.

China: Mobile first in the Internet of the Wild Wild East

While the Internet landscape had been well-paved by the time the App Store and the app world had launched in the United States, on the other hand, the Internet of China was still in its infancy. In 2007, at the release of the iPhone, less than 16% of the country’s population was online. At the time, Tencent, Baidu, and Alibaba were unbeknownst to the rest of the world, and China was chalk-full of copycat technologies that were too insignificant to be bothered with.

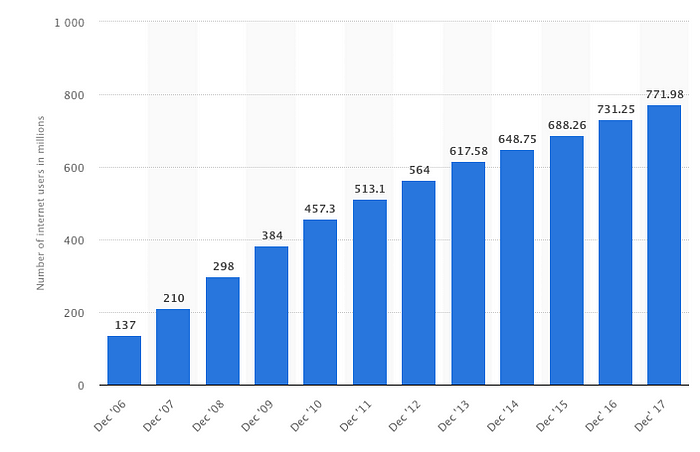

At the time of the introduction of the iPhone to China in 2009, the preexisting tech companies of the time had a unique opportunity to shape and mold the emerging internet consumer. With landlines and dialup being far and few between, “many consumers skipped the PC era entirely, going right to smartphones.” Within the 5 years following the release of iPhone in China, the number of Internet users in China increased over 65%.

For many of the Chinese, smartphones and the Internet were, and still are, one and the same experience.

Without preexisting notions of how their digital experiences should be, the Chinese consumer learned how to navigate their new connection to the online era under the guidance of the tech companies who had reached moderate success early.

However, as more and more of China took to phones to get online, Chinese tech companies not only became the guiding hand for the Chinese internet consumer, they also had Western tech giants to learn from. As Amazon took over the online retail world, Youtube and Twitch took online video sharing and streaming to flight, Apple, Paypal, and Square were putting more and more financial services online and on mobile devices, Tencent could pick, choose, and tune the same services for their ideal Chinese consumer.

While these services were innovated individually and fought for tooth and nail in the West before all-encompassing tech conglomerates could be formed, at the time, Chinese tech bigs could simply mold their idea of an app smorgasbord of social, ecommerce, online retail, and entertainment. With their established network value, financial ability to incentivize participation, they had no problem pushing out, or simply incorporating, insignificant individual competitors.

Let’s take a closer (abridged) look at how Tencent’s WeChat established its current form.

2011: Weixin launched as Tencent’s mobile only messenger (as opposed to QQ) with messaging and group messaging capabilities. 100m users, video clips, and soon to follow.

2012: Official accounts emerge. QR code support and features emerge to connect stores and brands from the physical world to the mobile online realm.

2013: Moments, Facebook-ish timeline, released. 300m users, and threatens Weibo as the social media app. The start of WeChat Wallet and mobile payments.

2014: Partnership with Didi Chuxing to hail cabs and rideshares right from within the app. Partnership with JD online retail marketplace to offer the JD store right within Wechat. WeChat stores feature released to allow any business to open a store within WeChat. User to user cash transfers and Red Packets. More than 100m registered Wallet users.

2016: Bike sharing within WeChat.

2017: WeChat Mini Apps/Programs feature released. Search engine feature released to go through all WeChat content. Subway system integration.

Note: Alipay (Alibaba) and Tenpay/WeChat Wallet (Tencent) have become codominant players in digital payments. An interesting story as well!

Facebook never had the chance to acquire Amazon, AirBnB, or Uber, because by the time it had the financial and network value to expand its offerings to ecommerce, financial services, and entertainment, those opportunities had already been taken by individual companies.

In contrast, in the development of the Wild Wild East, this perfect storm of the mobile first internet consumer, an underdeveloped storefront retail industry, and a model of successful tech to follow from the West, thrust Tencent and WeChat straight to the pinnacle of all these online offerings, bound together by its original social experience. But now, this social experience has people shopping, eating, traveling, and even paying their bills together.

Culture + Government: What WeChat needed to successfully bridge social with eCommerce that the US doesn’t have

Even as the stars aligned for WeChat to dominate a social and eCommerce integrated experience, WeChat has had two more factors that helped it build its empire: the Chinese concept of money as a social item, and the unique relationship of government and corporations with the Chinese people.

Adopting WeChat Wallet: Money is social

After seeing the incredible growth of cashless options, eCommerce, and online shopping in the West, China’s tech industry knew that the country was ripe for creating the infrastructure and experience that put all of these together. Without the strong, preexisting banks and credit card systems of the West, whoever could get all of China on board in unified system would take it all.

But how could Tencent make the push for their vision of China’s new mobile, online payment platform?

They took their chances with the platform that had already gathered people, companies, brands, and continued to expand as all of China took to the Internet: WeChat.

So how could Tencent incorporate a digital wallet into their primarily messaging and social platform? The answer was digital red envelopes or red packets.

Red packets, or hong bao, have a long and well-established tradition within China (along with many other East Asian and Southeast Asian countries). These ornately decorated red packets with gold embroidered characters representing wealth and fortune are monetary gifts to celebrate a holiday, weddings, or other social and family gatherings.

A year after the introduction of WeChat Wallet in 2014, WeChat helped celebrate the Chinese New Year by debuting WeChat red packets in a partnership with the Chinese Central Television Channel’s (CCTV) New Year’s Celebration, watched by an estimated 700 million people.

700 million people.

During the show, viewers with WeChat installed were prompted to shake their phones during breaks to win over $80 million (USD) in red packets. In one night, over 20 million users shook their phones over 11 billion times. In order to receive any gift money, users must have registered with WeChat Wallet.

Over this one six-day holiday, the number of users using WeChat Wallet more than tripled from 30 million to 100 million, and over 20 million red packets were sent.

And in just 3 years, Chinese New Years celebrations were filled with the crackling smoke of even more digital red packets in the air.

Even more, China’s established money giving tradition represents more than just a once a year occurrence. At the end of the day, in China, money is accepted, welcomed, and social communication.

Rather than feeling ashamed of handing over a 20 dollar bill or another Target “I don’t care enough to figure out something you’d like” gift card, in China, straight money exchange, and now digital money exchange, is the norm.

When joining a new group chat or social circle on WeChat, new members are welcomed by small red packets.

During Chinese Valentine’s Day, couples might send 5.20 yuan to each other to signal their love. 5.20, 五二零, wu er ling, wo ai ni, 我爱你。I love you.

China, through its culture and history, has built a unique environment for the melding of word-based messages and the implicit communication passed through money exchange. Through ingenious development strategy, marketing, and leadership that play to Chinese idiosyncrasies, WeChat in 5 short years, was able to transform itself into a mobile payment player that is practically universally accepted, alongside Alipay.

With WeChat Wallet adopted, Tencent merely had to take a short walk to leverage its huge network of digital consumers to expand into eCommerce offerings like JD shopping, WeChat’s online shops, ride sharing, hotel booking, food takeout, and more.

Privacy and regulations: Why China supports super-apps

Even with the opportunity to take and customs playing into the hands of Tencent, an equally important, if not even more important consideration into the rise of super-apps has to be how the Chinese government, and in turn, the Chinese people examine these growing tech and app ecosystems. With the Western world turning to heavier privacy protection policies, the United States’ antitrust apparatus preparing to do battle against Big Tech, and growing skepticism from the public in the West, where does China fall within all of these lines?

At the end of the day, they don’t.

In the US, privacy has its roots in the very founding of the nation itself.

“If you want to talk about privacy, what would be less private than having a platoon of Redcoats living in your house, eating your food, listening to your conversations?” says Neil Richards, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

The formation of the US government was done precisely in opposition of an oppressive government. The people are fundamentally opposed to the government. We maintain the right to: assemble, have free press, oppose quartering, protect against unreasonable searches and seizures, maintain “a well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State…”, [and] “…keep and bear Arms.” This opposition is fundamental in the system of checks and balances.

With privacy and oversight in the blood of the US, recently tightened data privacy requirements in the EU, and Cambridge Analytica just behind us, people are more and more reluctant to take part in all encompassing data collection. Imagine not only having your location, friends, conversations, and interests gathered, but also those in tandem with your shopping habits, your banking information, your travel plans, food preferences, work life, and traffic violations.

In fact, China is experimenting with an all encompassing citizen identification system, the Society (Social) Credit System that is intended to be rolled out by 2020.

This concept of privacy and that only the parties directly and voluntarily involved should have access to related informations heavily leans into the individual app culture in the US and in the West. However, on the other hand, privacy with regards to the government and similarly tech companies, have a much different history in China.

Even today, much of governance has its roots in traditional Confucianism. In Confucian society, the state had its model in the family. There was an intrinsically intimate and overseeing role for the state to lead in educating and transforming the people. In modern society, the Chinese term for state is “guo jia” or “nation-family”, “suggesting the survival of the idea of this paternal and consensual relationship.”

Rather than being inherently opposed against the state, the Chinese people accept the government as much a part of the home as any family member.

This concept transforms the idea of privacy in Chinese government. Data collection and usage are the government’s, in tandem with tech companies’, efforts to educate, protect, and promote the long term success of the nation. Even as some citizens are voicing their maturing understanding of Western data privacy concerns, can eras of history and decades of government censorship be that easily overturned? For the regular Chinese citizen, data collection still exists as:

If I do no wrong, no problem.

Then taking a look at super-apps with this concept in mind, I, too, would be happy to sacrifice privacy for convenience.

Another topic worth noting is China’s antitrust practices. Are there concerns with growing monopolies and a few absolute tech behemoths in the arena? Historically, Chinese antitrust laws have typically been put in place to limit the influence foreign multinationals can have domestically rather than to promote a more competitive marketplace. With Chinese big tech’s close ties to the government (as highlighted in CCTV’s CNY WeChat Wallet promotion), the Chinese government is more likely to continue to support and in turn, maintain influence, on the companies that have lifted China from the ignominy of a cheap labor nation to the leading visionaries of what cutting edge technology can be.

What tech should look like, and what it’s relationship should be with its constituents are being defined right now in China. With influences from the Confucius state, and the huge ambitions China has to reclaim its former glory in its “Chinese Dream”, super-apps are creating an experience bigger and more all-encompassing than ever seen before.

So if super-apps have no hope to follow the same recipe as WeChat or other Chinese super-apps in the West, what am I doing here? What’s really next?

The future of Big Tech’s super-sized ambitions in the West

Not everything is bigger in America, but that doesn’t mean that the app experiences of the West aren’t big. Facebook by way of Messenger allows you to send money to that friend that you always lose NBA playoff bets to. Now from Facebook events and pages, you can go straight to Ticketmaster to purchase tickets for Radiohead’s new tour, or navigate to OpenTable to reserve a seat for a special night for two. Facebook is investing in Oculus, as VR is one of their big bets for the future of social platforms.

OAuth has enabled both Google and Facebook to power login services almost universally.

Amazon is partnering up with studios and producing original TV series to add to their entertainment offerings. Whole Foods is now a part of Amazon and their Prime/Now delivery offerings.

Within the individual app culture in Western tech, what I see is rather than super-apps, we have super-connectors.

Western tech giants are becoming, if not already are, the Autobahn super-highways of the Western Internet. While not being able to provide the same, seamless UX across all of the pieces they connect, from their app experiences, directly to the relevant ticketing page, dining reservation, or pair of jeans you’ve been eyeing for months. They provide a portal that bypasses company landing pages and login fluff straight to the specific desired item, even if it’s offered by an external service.

So what’s next?

Social x eCommerce

The biggest difference in Western tech giant’s abilities to grow compared to those of Chinese tech giants is the lack of a social and shopping/financial services experience.

Social media app users have no desire and quite possibly are opposed to financial services offered by those social media giants. eCommerce and online retailers have no access to the viral effect of social platforms to encourage platform adoption. While we can see Facebook slowly attempting to wrap its users into the money game with sending money to individual friends, how many of us are onboard?

Social media companies must look not to the individual users that might sign up one at a time, but at platform influencers. Facebook with Instagram and Youtube could look to play into the brand aspects of their platforms to provide online stores, loyalty programs, or way to directly showcase and purchase fashion wardrobes or promoted products. These platforms might provide tools for newer brands that primarily grow through these platforms to directly interact with consumers. Rather than having to set up an online store through Squarespace or offer promo codes to other vendors, why not allow them to have your platform be their all-encompassing home base?

Amazon might look to invest in growing towards a social shopping experience. First, allow a group shopping and ordering to allow people to save on shipping or grab bulk deals with friends. Then, continue to move into a more social shopping experience to share, gift, and promote things with your circle.

Each of these of course require large infrastructure investments or acquisitions to get off the ground. But what better way to leverage your existing success, established networks, and excess cash for longterm, albeit ambitious, growth?

Infrastructure for an increasingly mobile first experience

Even as the United States does not have a primarily mobile first internet consumer, there is without a doubt a growing shift away from hulking machines that hide in our homes and backpacks, and towards accessible and available mobile devices.

Right now, these super-connector companies often provide more than a few inconveniences when trying to connect on mobile. Google Maps might ask you to —Would you like to Open the App Store? — or otherwise open another app, Facebook might direct you straight to the browser, and specifically to that other browser that definitely is not my default browser. After another minute of signing up and signing in, then trying to press the little browser links — I’d decide to pull out my laptop instead.

I don’t want to have to endlessly download, open, login, insert payment information, and then close apps for once a month activities.

I’m expecting, or maybe just hoping, that these super-connectors start investing in infrastructure and APIs to offer small, incremental in-app experiences for one-off things like ordering, menus (Google Maps has this already!), and event ticketing. From there, they might be able to offer comparable mini-apps as WeChat has successfully experimented with.

In the meanwhile, as consumers, let’s keep our tinfoil hats on to stay aware, cautious, and calculated. Rather than being a victim of aimlessly accepting terms and agreements and providing personal information, let’s take an active part in understanding, and voicing our opinions, for when the tradeoffs between privacy and convenience are, and aren’t worth it.

I’ll be writing more about interesting Chinese tech and trends soon. If you want to stay in the loop for more East meets West tech crossovers, follow!