What I learned in (almost) 30 days of Codevember

What is #codevember and why would you do it? For the past couple years I’ve noticed interesting generative art popping up on social media in November with this hashtag. According to codevember.xyz:

Codevember is a challenge for developers to sharpen their creativity and improve their skills. The goal is to build a creative piece of code every day of November. We give you daily hints to inspire you but you can do unrelated sketches.

This year I decided to give it a try, and use November as a time to learn Processing (p5.js)and indulge in making graphics that don’t have to serve any particular purpose.

👉 it’s better to do the pre-work subconsciously

Days when I had a question, form or pattern in mind were better. I arrived at the hands-on coding with something partly formed, which reduced the work down to getting the code functioning, and experimenting until it looked good. Days when I started coding with no real idea of direction were harder.

I had browsed Daniel Schiffman’s Nature of Code before. He starts with Brownian motion and flocking behaviors, which I thought could be used to position the “pen” for drawing.

👉 momentum is effective

Keeping a regular cadence kept me familiar with the syntax and thinking along the lines of evolving sketches over a few days, instead of starting from scratch each time. Even though this sometimes felt like a cheat, in some cases I was happy with the results.

👉 it’s easy to fit in to your day, but hard to fit in every single day

I was pretty consistent, but there were a few days when I missed one and caught up with two sketches the following day. There was one day I missed and didn’t make up. With a family and full-time job, squeezing in a new daily habit that can take up to 30 minutes was not always plausible.

👉 daily sketches are not the best way to learn a new(ish) language

Given my time and attention constraints, most of the learning I did with Processing was fairly rushed. I leaned heavily on the reference page to plant seeds for what’s possible in p5.js, and in many cases borrowed and adapted code to get things going. Which worked, but I didn’t have enough time to gain much real fluency.

👉 I favor a particular color palette

One thing with color that was great with p5 is the HSB (hue, saturation, brightness) color space. It’s much more intuitive than RGB (who thinks in terms of how much red, green and blue are in a color?) or hex colors. Despite having access to this new method for coding color, I almost always gravitated back to familiar color habits. Not that it was a bad thing, just something I became more aware of.

(And now I see I’ve been overlooking HSB/HSL color mode in d3.js for years!)

👉 complex systems are the sweet spot

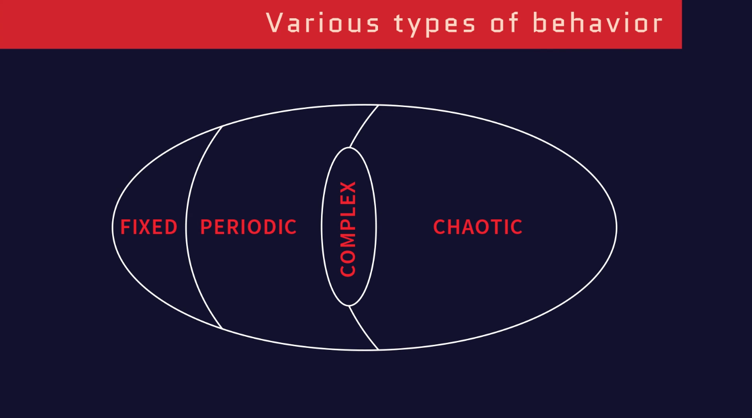

Several days in I found an online course called Generative Art and Computational Creativity from Philippe Pasquier, which I’m still making my way through. There’s a much deeper and wider history to generative art than I had imagined, and refreshingly, there’s a formalized taxonomy to take into account. This diagram of classes of behavior of generative systems clicked for me and informed what I was looking for, and why I would sometimes take a fairly long time to decide a sketch was “done.”

Fixed systems produce a single static output; periodic systems oscillate between two or more regular states; chaotic systems produce no predictable pattern (I suppose here we are not including things like strange attractors), but complex systems give us the framework and stability of periodic systems with the organic randomness of chaotic systems.

👉 using things wrong can be a strategy

At a few points I got stuck trying to make things work in 3D, and just through sheer tinkering with code eventually ended up with something that wasn’t what I was trying to do, but was interesting enough to call it a sketch. Instead of moving a 3D shape through time I was drawing alterations of that shape repeatedly on top of itself, which created a composite shape.

I’m inspired by David Hockney’s amazing composite polaroids : a painter takes picks up an instant camera and instead of taking pictures the right way, ends up with a fractured dragonfly-eye-lens, time-agnostic viewpoint that couldn’t have been created without using that technology “wrong”.

👉 I hew towards organic disruption of beautiful math

Perfect forms are pretty, but disconnected from experience. Intrigue lies in the flaws: where did that lovely plan go wrong?

By describing and creating systems that balance structure and procedural rules with noise and randomness, I’m working closer to making things that reveal beauty in unexpected ways.

It’s entertaining to watch these sketches draw themselves. View the full collection.