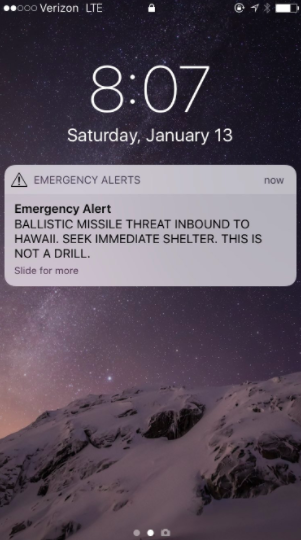

Recap: The people of Hawaii woke up to a terrifying alert Saturday morning across their phones, radio, and TV screens: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

Understandably, everyone freaked out. Kids were dropped into sewers. Investigations were launched. The conclusion to those investigations? The Governor of Hawaii claimed “human error” was the root of the problem.

Blaming “Human Error” is the Easy Way Out

Blaming human errors is really easy. After all, many disasters are caused by “human errors”—From car crashes to plane crashes to nuclear reactor meltdowns. After all, blaming the error on some hapless person and firing them is easy. It makes people think the problem is fixed.

But blaming the person doesn’t actually fix the problem. The Honolulu Civil Beat posted this mockup (this is not the real interface!) of the interface that caused the error. Can one really blame the person for clicking the wrong link?

Yes, it’s a design problem

If something is clearly confusing, it’s a design problem. If something that should be easy is very difficult, it’s a design problem. If mistakes can easily be made, then yes, it’s a design problem. If you can’t undo those mistakes (before causing widespread panic, death or nuclear meltdowns), it’s still a design problem.

With some foresight, good design should predict and prevent people from doing dumb things.

Yes, it’s a fixable interface problem.

It’s easy to blame bad design on bad interfaces, and in this case, the mistake could have easily been prevented with a small tweak. It doesn’t need to look gorgeous, or even be Dribbble-worthy. Here’s an example:

The main problem of the interface boils down to: “Why are the real, hard-to-reverse alerts mixed in with the demo and test links?”

Help the user out by grouping the links with context. Add some colors. Add some threats to fire the user if they do something dumb, on purpose. Don’t let the person do the dumb thing in the first place.

Note the false alarm link they added after the incident. It’s the “just kidding” button. Like the sorry I didn’t actually mean it when I said I wanted a divorce, button. Once the message is out; once the bell has been rung, you can’t unring it. Don’t ring the bell in the first place. Make sure the bell-ringer knows all the consequences.

Apparently, they also had a confusing confirmation screen. Look, it’s not hard to dissuade someone from making a horrible mistake with a confirmation screen. Display the entire message you’re about to send:

You are about to send this alert to EVERYONE in the state: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

Give the user two options, the first one is innocuous, the second one in big red, scary letters:

- No just kidding, don’t send the alarm. Get me outta here!!

- YES. Send this horrible alert to the entire state. NOT A DRILL.

Also if this is a mistake you’re totally fired.

Don Norman probably had something more legitimate to say about it. After a quick Google search, yes he did and it’s great and you should totally read it.

It’s more than just design.

Of course, if they had hired Don Norman in the first place, this probably wouldn’t ever have happened. Why didn’t they? Or why didn’t they hire a decent designer? Who knows.

The problem probably stems from the people who probably hired the lowest-bid contractors to not do the job as specced out, without putting in an ounce of extra thought.

Funny enough, Alaska retorted that they had a better system:

“We don’t have a simple button that you would hit, and it could be the wrong button,” Sutton said “We have to manually create the message, type in a password, click multiple buttons and then, before you transmit, the system is going to ask the operator to type ‘yes’ before you are allowed to actually proceed.”

And maybe this system is “better” in that it prevents errors. But if everyone’s dead by the time you’re done hand-crafting a clever message, it’s not really much “better.”

More Useful Alerts

Note: I don’t work in emergency management, and these are just my rambling thoughts.

An alert system doesn’t just warn people of missile strikes, but also of hurricanes, blizzards, flash floods, forest fires, and who knows what else.

To be fair, the message itself was decently clear: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.” It conveyed the following:

- Describes the incoming threat. What and where is the threat?

- What’s the timeframe of the threat? Is it now? Is it this evening?

- What should people do? Don’t leave people hanging.

- It’s not a drill. (At this point, no one will probably take “This is not a drill” seriously anymore. But if it IS a drill, please tell people it’s a drill!)

The message should say: What is the threat? When is the threat? What should you do? Any real situation might change over time, and people like to stay updated: what are the AM/FM radio stations, TV stations, and links to a dedicated website and twitter feed? Find other avenues to give more information. Put it on a website; post it on twitter. Give people a situation report; tell people what actions they can take:

- Where to find shelter?

- What are the escape routes for fires and hurricanes?

- What food/water to pack?

- What are the weather conditions?

- What are the next steps to you should take?

- What is the timeframe? e.g. for a hurricane, pack a 1–2 weeks of stuff

- What happens if you don’t take action?

Learning Process

Bad design only really rears its ugly head when someone makes a mistake. This Hawaii incident is a reminder for organizations to review their procedures and interfaces. Take a look at what could be confusing, or what could lead to bad mistakes. Test them by putting people under immense pressure. It could save your organization a whole lot of embarrassment—it could even prevent a nuclear meltdown!