Designing for Progressive Disclosure

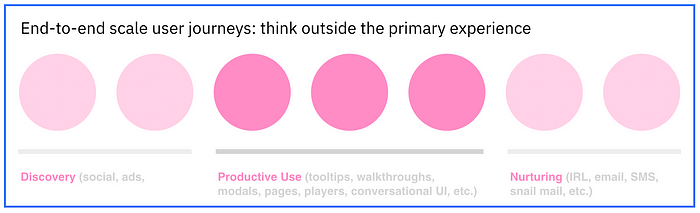

A few weeks ago, I gave a presentation at General Assembly alongside Michael Lee Kenney about designing for progressive disclosure. At its core, progressive disclosure is about moving a user through an experience in a way that escalates from simple to more complex, showing only the necessary and relevant information at any single point in time.

Progressive disclosure should not be thought of as an exclusively digital approach. It is quite literally the progressive disclosure of an aggregation of experiences, regardless of the medium. A well designed architectural floor plan is an excellent example of progressive disclosure; moving a person through space and time in a way that is additive in both awareness and value.

I’ve worked with several designers who may not have been familiar with the term ‘progressive disclosure’ but who were already designing products and experiences with progressive disclosure in mind. However, taking a more intentional dive into this approach will help new and experienced designers alike review their work with an additional level of awareness. As experience designers and researchers, we want to focus not only on the product or service design, but on the utilization of both written and visual content as well as methods for escalating user interest from inception through to a resolution.

Edit: Read the second part of this progressive disclosure series, Progressive Disclosure Part II: product design workflow here

Definitions and examples of progressive disclosure

There are many different methods for progressive disclosure that focus on revealing information in a way that mimics how our brains understand and process new content. While leveraging certain archetypes can at times be the best solution, we also want to design unique or case-specific methods for progressive disclosure that pull inspiration and insight from a variety of fields. Let’s start with some traditional examples and then broaden our perspective to other experience design methods.

1. Featured snippet

This method is a progressive disclosure staple for software and digital content designers. This snippet presents the user with just enough information to determine if they want to dive deeper and take an additional step to learn more, or if the information provided already meets their needs. Additionally, the information provided may not be relevant to what they were looking for and the user can redirect their efforts early on without spending too much time sifting through content to make a decision. Other similar approaches include truncated content and content previews.

2. Expanded detail

Some users want to find out how a particular capability works. Perhaps it is critical for their job role, particular user goal, or an integral way in which they understand the world and processes around them. But other users are the opposite. Depending on the task or content, many users may care less about the how and be far more focused on what they need to do to get a discrete outcome. We don’t want to burden this group. Since digging deeper for more information is integral to how the first user group moves through understanding, we can ask them to take an additional step. Anything warranting “learn more” or “see how it works” will fall into this pattern. Michael Lee Kenney describes this group of progressive disclosure patterns as achieving the “Goldilocks” level of content consumption, where you have just enough but not too much for each user type or interest level.

3. Lazy load

While the pros and cons of infinite scrolling can be debated on both tactical and existential levels, the lazy load is a nice counter-balance to the influx of constantly available and never-ending content we find ourselves presented with in digital mediums. This idea that, “they want it all and they want it all now” may be what users say, but it’s our job as researchers and designers to figure out when this is really best. The lazy load gives the user reassurance of requested content without overwhelming them in a way that dilutes the quality and value of the content itself. During our presentation, Michael Lee Kenney drove home both the practical and experiential value of the lazy load:

There is also a practical value when it comes to webpage load times. Loading the most relevant content provides immediate access to a “full” experience. 90% of the people only want 10% of the content. Forcing EVERY person to wait until EVERY piece of content loads before they can consume your experience will lead to a higher bounce rate.

4. High end dining

Let’s shift our focus to the original curators of delightful experiences. High end restaurants have perfected anticipation around eating and savoring delicious food that is presented with the same finesse and restraint as an art exhibit. Without a doubt, patrons want to eat the entire meal. But to be presented with the entire meal at a single point in time would result in a complete loss of procession, palette and storytelling. Curating what to present first and the order of what’s to follow has multi-sensory implications on the patron’s impression of the dining experience.

If we use the example of high end dining, we can see how progressive disclosure begins at a distance from the core experience. Whether this distance is physical, as in the case of approaching a restaurant, or sequential as in finding your way to and through an application, we want to think about the user’s experience through space and time, recognizing how important the lead up can be for the mindset, contextualization, and ultimate appreciation of a core experience.

5. Product unboxing

Product unboxing is a fundamental progressive disclosure design challenge. The way in which the box physically opens, the presence or lack-thereof of written or visual content presented at various stages in unpacking, and the ultimate relationship between the physical product and how the user understands the product to be used all work together in the creation of an experience. The designer needs to ask themselves, how much information is necessary and at what stage? How can I balance branded information with usage information? These same questions can be asked by digital and software designers as they move a user through an application.

Again, I want to emphasis the importance in drawing inspiration for progressive disclosure from a variety of sources by extracting the most effective elements of each example and recognizing that the same principles used in high end dining experiences can be abstracted and reapplied towards a custom application design for an on-boarding user flow. The content and mechanics may be different, but the experiential approaches can be surprisingly similar.

Progressive disclosure principles from above examples:

- Do not overload the user with all available information upfront.

- Incorporate elements of suspense, progression, and surprise with the appropriate information at the appropriate time.

- Ensure that each subsequent step in a user’s flow builds on the previous step in both consistency, user goal, and value.

- Ensure the type of content is aligned to the method for displaying and revealing that content; do not try to retrofit the content into a specific design archetype.

- Do not assume you know what the user wants to see first or values the most; ask them (more on this in the next section).

- Map out the entire user flow, especially the events that take place before and after your product. See how you can connect all of these experiences seamlessly, moving from simple to complex.

Starting with user research

When conducting user research for progressive disclosure, there are some specific tactics you can implement to inform your design. The first is expanding your list of ‘users’ to include customer service reps and sales reps! In general, if you are conducting user research and are not currently working with these people, reach out asap and get to know them. They are immensely valuable because they talk to users all day. Every day. And their discussions with users often center around progressive disclosure. They are either the point of contact for the user when information is not presented clearly or the last point in an escalation of progressive disclosure where the final step is getting help from a live person.

I also loosely recommend two discrete rounds of user feedback for progressive disclosure. The first round is critical. You MUST ensure that your design team, your stakeholders, and your users are all aligned on the most important goals of your offering. If not, you are not ready to design, and you will progressively disclose the wrong information with incorrect hierarchies and procession.

Let’s take an example from above. For high end dining, it is important that the restaurant owners, chefs, and patrons all agree that while the point of this specific experience is partially to quench hunger, it has a higher purpose: to entertain and delight. Without this mutual understanding, it would frustrate hungry patrons who are not interested in multiple courses, ambient lighting, and long-winded dish explanations. The design of the experience is not for anyone who is hungry. It is for users who are hungry and want an experience to remember and the creation of memories.

Let’s take a software example. For the website Eventbrite, the user interface is heavily geared towards users looking for events. Users who wish to create events have to dig deeper. That’s because the most important value that Eventbrite provides, is finding events. It is not an event creation app, although it does contain that capability. If there was a lack of alignment about the hierarchy of value propositions between Eventbrite designers, stakeholders, and users, the site’s purpose and information revelation pattern could be completely amiss.

The second round of user research focuses on testing the hierarchy or user goals so that they are properly displayed and presented in your design. This can be done with a combination of interview questions, low-fidelity prototypes or existing product assets. It’s about having a conversation with users and playing this information back to stakeholders. Next, you want to ensure that any multi-step flows that reveal information progressively are designed in a way that is understandable, logical, and enjoyable. While some information, say about problem solving or “how it works” is more reliant on being logical, other types of information like “music shows in your area” are more reliant on being both understandable and enjoyable. Again, this comes back to content-led design! Not the other way around.

As you and your team work to develop interaction patterns and progressive disclosure methods that speak to both your content and your brand, remember this: progressive disclosure is not a one and done exercise. It is a holistic design approach and is ongoing in nature.

Progressive disclosure is not a one time activity…as the goals and capabilities of an offering evolve, so should the portrayal of content and complexity.

Applying design thinking to progressive disclosure

If you and your team are wanting to design for progressive disclosure or you want to push the boundaries of your current progressive disclosure methods, frame it as any other design problem. Apply design thinking methods just as you would when trying to solve a specific user need. Co-create progressive disclosure flows with target users, create low fidelity prototypes and test. Then test again and refine with every release or every change in product scope and capability. Whether it’s a product unboxing or an enterprise technology application, the way in which a user moves through your experience is a design challenge to be solved with iterative prototyping. It’s not a check box on a usability list or a plug and play from a list of archetypes. Each and every product will require a refined look at how information is progressively disclosed, and having this perspective opens up the possibilities and variability that you can bring to your product, even when a user is simply trying to see how a specific feature works.

As you and your team get started, try and think of some ways in which you’ve encountered progressive disclosure in your life. Comment any ideas or thoughts below, and be sure to think outside the boundaries of your product or service! You will quickly realize the inspiration you can draw from a variety of mediums you already experience every day.

Edit: Read the second part of this progressive disclosure series, Progressive Disclosure Part II: product design workflow here

All thoughts expressed are my own. http://www.gabriellacampagna.com/